Pirates of the High Cs

September 2002This article is part of the Noteworthy News archives.

The music industry is aghast: anyone can reproduce their product for free and they appear powerless to stop it. Sounds familiar, except the decade is the 1890s and the problem isn’t unauthorized digital duplication and file sharing, it’s record piracy.

Record piracy was a widespread and recognized, if not necessarily honorable, profession. It was practiced by entrepreneurs large and small, by local dealers whose names will be forever unknown who stole from big companies like Edison and Columbia, as well as by big companies like Edison and Columbia who stole from each other.

It was easy and profitable. And at least until 1909 it was very much a gray area of the law. The copyright act of 1870 said nothing about who owned the rights to a recording, because in 1870 there was no such thing as a recording. The copyright office continually refused to register copyrights on records, on the grounds that records were not a writing within the terms of the copyright law.

The aggrieved party might have had some remedies under common law, but they were largely ineffectual. He had to prove a sort of unbroken chain of piracy -- not simple when, say, the matrix numbers and all other identification had been rubbed off the record.

There hadn’t been any piracy problem with the tinfoil machine, because the records fell apart when removed from the mandrel, and, anyway, the dismal sound quality was suitable only as a novelty. The dilemma began when Bell and Tainter introduced the wax record, and Edison followed with his own version.

The early brown wax records were made up to nine or ten at a time, the musicians blasting into a set of recording horns. Some records might sound better than others because of their placement in the studio or the way in which the recording engineer adjusted the recording stylus, but the records were all originals. Columbia advertised that one popular title had been recorded 38,000 times.

Musicians were paid by the round --there was no concept of royalties. (The tenor Francesco Tamagno was the first to receive royalties in 1903.)

Why piracy began

In the early 90s all the phonograph companies were consolidated in a trust nominally owned by a businessman named Jesse Lippincott, and regional territories were established by analogy to the telephone company. It quickly became evident that the phonograph was not appropriate for business purposes as the founders of the trust had conceived, but also that the demand for records as entertainment in coin-in-the-slot machines was insatiable, greater than anyone had dreamed.

Lippincott had thought to retain the right to manufacture musical records but hadn’t done so. It wouldn’t have mattered. Edison couldn’t output records fast enough to keep up with demand. And so of necessity the regional companies began to make records, acquiring thereby all the attendant technical expertise and machinery.

A mechanical way to duplicate records had to be devised, and it first appeared around 1891. It was also the only weapon that the record pirate would need in his arsenal: the pantographic machine.

The first pantographic machines were probably made in company machine shops. You couldn’t order a duplicating machine out of a catalogue, or buy one at any price. It was a zealously guarded trade secret. Edison removed his from his factory to a separate building, because he feared the secret would be spilled within two weeks. The Chicago territory kept its behind an iron chain, in a locked room with a skull and crossbones upon the door!

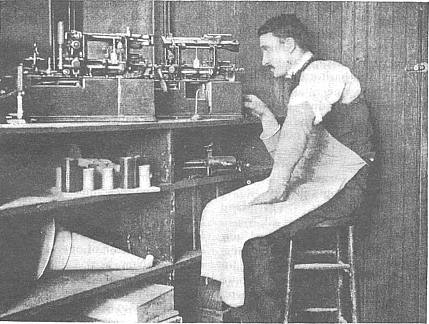

Bettini laboratories, tinkering with the duplicator. This pantograph was patented by Bettini himself. Courtesy Allen Koenigsber)

Big companies like Columbia bought up the patents to duplicating machines and attempted to confiscate machines used in prohibited activity. Sometimes they would lease back rights, as they did to the Chicago territory’s Leon Douglass, inventor of one of the first pantographic machines. Douglass’ pantograph was not much more than a vacuum hose connecting two phonographs, but the factories might have banks of machines driven by pulleys from overhead shafts.

Duplicates were felt by the public to be of lower quality. They were often marked as duplicates in the catalogues and sold for less, around 75 cents or a dollar, around half the price of an original.

The temptation to make unauthorized duplicates must have been irresistible, the economics overwhelming. In the 1890s Edison calculated the cost of making a record --the cost of a blank, the cost of the musicians, the cost of heat in the studio--at around 34 cents. The retail cost of a blank was around 25 cents.

Blanks were easily obtained; Edison even sold his to Columbia. Or you could make your own. As early as 1891 Edison’s spy Joseph McCoy caught Isaac Norcross duplicating records, melting down old cylinders and adding Ivory soap to the brew!

A Golden Age of piracy

Any small businessman could sit one machine in front of another and record, and probably did, but there is no record of such subterranean activities, which were probably quieted by the threat of a lawsuit. The regional companies unabashedly stole from each other, while denying it as best they could. “Pirates in this business not only steal ideas, they steal entire records also,” bemoaned the October 1898 Phonoscope. “In no other business is it so difficult to reap the reward received.”

The Chicago Central territory was conceded to be the epicenter of the mischief, a gang whose specialty was the illicit duplication of records. In 1892 Columbia’s Edward Easton alleged that Chicago Central was the most likely originator of bogus Columbia titles. There wasn’t an effective remedy. When some spurious Chicago Central duplicates of Edison recordings were presented to Edison, all he could do was pooh-pooh the quality of the sound, and tell the complainant that if he was satisfied with that quality record, he should buy it directly from Chicago Central.

Edison, too, borrowed from his competitors. In 1892 his agent Walter Mallory secretly purchased a number of vocal and band titles from Columbia, titles which thereafter appeared in the Edison catalogue. Edison’s secretary, Tate, secretly ordered titles from the New York and New Jersey regional companies.

Columbia filched music from the United States Phonograph Company and sold the duplicates as originals. And James Andem, owner of the Ohio territory, insisted that Columbia was stealing his series of Pat Brady recordings.

Since cylinders were sold in plain pasteboard boxes until 1898 there was no wrap-around label to serve as a guarantee of the record’s authenticity.

The voyage of the flat disc record in many ways mirrored the history of the cylinder record. Almost from the inception, the record brigands attacked. Record researcher George Paul discovered a series of Zon-o-Phone records so identical to Berliner’s records that they appear to have been pressed from the same matrices.

Pioneer booty:The title on the bottom, a replica of the Berliner recording, may represent the earliest known piracy of the flat disc record.Courtesy George Paul

It would not have been difficult to copy disc records. Anyone in the printing business would be capable of doing the type of electroplating necessary, and by 1906 Duranoid and at least five other companies were capable of pressing the shellac.

Illustrious pirates

Most record buccaneers remained discretely anonymous, few as celebrated as Bluebeard or Sir Henry Morgan.Two of the most brazen known swashbucklers were Joseph Jones and William T. Armstrong. Armstrong had been involved with the Double Bell Wonder machine; Jones as a young man had worked for Berliner and had stolen Berliner’s electroplating secrets. Their Vitaphone label was the scourge of the industry for years.

Another notorious thief was Winant V.P. Bradley. Not an unintelligent man, he held several patents and had been somehow involved with the piracy of the early Berliner records. In 1902, along with some Ohio investors he fathered the Talk-o-Phone company, but when Talk-o-Phone began to turn sour in 1906 he returned to his earlier vocation of record piracy. The Leeds and Catlin company had been locked in a long legal battle with Victor and Columbia over duplicates of recordings pressed outside the United States. Relying on a court decision that led him to pretend it was permissible to do the same, Bradley established the Continental label. He was an honest pirate: each record forthrightly warned that it was a duplicate of another.

Repelling the broadsides

Many strategies-- mostly ineffective--were employed to deter the record pirates. The announcement was run as close to the music as possible, or into the music. In Europe, the Recording Angel was embossed between the grooves, also serving as a form of trademark protection. Berliner, in Canada, briefly tried the same tactic with an image of Nipper. (Nipper stood guard for only a few months --perhaps the trademark introduced too much static into the record.) Columbia tried to buy up all the duplicating patents and sue for patent violation. The legalese of a lease was printed on the records--copy the record and break the lease.

In 1903 the issue of piracy of the cylinder record was rendered moot not by the law but by technology, by Edison’s brilliant new gold molded records. Then in 1906 Victor won an important Federal case. Victor got the court to say that Vitaphone’s use of a red label amounted to unfair competition, confusing the public with Victor’s prestigious red label. Both Vitaphone --and later Bradley--were enjoined on the basis of unfair competition.

Nonetheless the law was still quite murky, until in 1908 a case finally worked its way to the Supreme Court involving, of all things, the Aeolian company and perforated piano rolls. The court ruled that a composition’s copyright was not infringed by manufacturing piano rolls.This decision applied by analogy to records: there could be no copyright of records.

Congress responded by writing the Copyright Act of 1909. For the first time copyright was granted --not to the record itself but to the composer. But there was still a problem. Aeolian had been greedily buying up composers’ copyrights, attempting to create a monopoly in anticipation of the new law. So the law was amended so that anyone could pay a royalty to the composer. It worked so well that the record pirates hardly hoisted the Jolly Roger for another 90 years.

Sources:

Paul, George. Mt. Morris, NY. Interview;

Paul, George and Fabrizio, Tim. The Talking Machine, An Illustrated Compendium.

Wile, Raymond. Record Piracy. ARSC Journal, 1985.

Koenigsberg, Allen. The Patent History of the Phonograph.

Feaster, Patrick. American Exhibition Recordings and the Dawn of the Recording

Industry.

Brown, Glenn Otis. Running For Cover.The New Republic Online, posted 7/21/00.

Copyright 2016 Vicki Young

Vicki Young

Box 435

Randolph,OH 44265

330 325-7866

We buy, sell, and repair antique phonographs and music boxes.

Pick-up and delivery possible in many parts of the midwest, south, and northeast.

Mechanical music

for sale

Resources

Resources

Contact/

Contact/